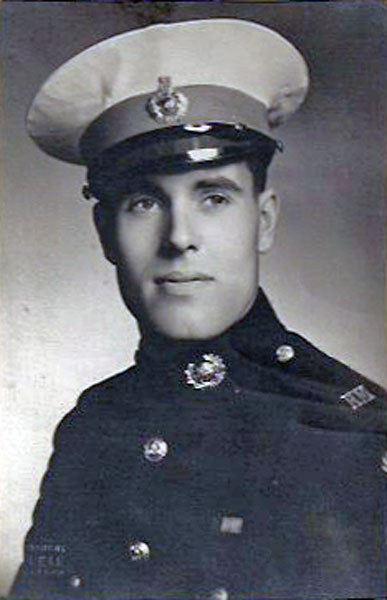

William Purdy

William was a Royal Marine, RM X2467, who served on HMNZS and HMS Gambia from February 4, 1942 to July 11, 1946. As well as Gambia he also served on HMS Resolution and Kenya. He sadly passed away in 1982 after suffering many years of illness as a result of being on board two separate ships blown up, including the torpedo attack on HMS Resolution (September 25, 1940).

William was a Royal Marine, RM X2467, who served on HMNZS and HMS Gambia from February 4, 1942 to July 11, 1946. As well as Gambia he also served on HMS Resolution and Kenya. He sadly passed away in 1982 after suffering many years of illness as a result of being on board two separate ships blown up, including the torpedo attack on HMS Resolution (September 25, 1940).

I am very grateful to his son, Garry, who sent the information and images for this page.

William was attested into the Royal Marines in Derby on May 31, 1938. The notice of attestation reads:

The General Conditions of the Contract of Enlistment. that you are about to enter into with the Crown are as follows:-

I. You will engage to serve His Majesty as a Marine in the Regular Forces for a period of 12 years from the date of Attestation, if 18 years of age or upwards; but if under 18, then for 12 years in addition to the period which will elapse before you attain that age.

2. If your term of Service should expire while Serving on any foreign station, the same may be prolonged for a period not exceeding 2 years. as shall be directed by the Admiralty.

3. When attested by the Justice you will liable to all the provisions of the Army Act for the time being in force, subject to the modifications for Royal Marine Forces.

4. If you are a soldier of the Territorial Forces, you will, on enlistment for the Royal Marines, be deemed to be discharged from such Force. You will, nevertheless, be liable to deliver up (fair wear and tear only excepted) all arms, clothing, and appointments, being public property or property of the Corps, issued to you, and to pay all money due or becoming due by you under the rules of the Corps, or to placed under stoppages until the value of such arms. clothing. or appointments not so delivered up, or such money is fully paid.

5. If within three months from your attestation you pay for the use of His Majesty a sum not exceeding £20 you may, at discretion of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, be discharged.

6. You are required by the Justice to answer the questions printed on the back hereof and you are warned that if you make at the time of your attestation any false answer to him you will be thereby liable to punishment.

King's Badge

On March 7, 1918, His Majesty King George V visited the Depot Royal Marines, at Deal in Kent. On this occasion he inspected Royal Marines Recruit squads, and took the salute of the 4th Battalion at a March Past. Six weeks later the 4th Battalion were to storm ashore on to the Mole in the raid on Zeebrugge, where they won great fame and two Victoria Crosses.

To mark his visit, His Majesty directed that the senior Recruit Squad in Royal Marines training would in future be known as the King's Squad. He also directed that his Royal Cypher, surrounded by a Laurel Wreath, would be known as the King's Badge, and would be awarded to the best all round recruit in the King's Squad, provided that he was worthy of the honour. The badge was to be carried on the left shoulder, and worn in every rank. Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II was graciously pleased to approve that the custom and privilege of the King's Squad remain unaltered. The King's Badge is not awarded to every squad, and is only presented if a Recruit measures up to the very exacting standards required.

William Purdy took part in the invasion of Norway in 1940. Here is an account of the action he was involved in taken from "The Royal Marines: The Admiralty Account of Their Achievement 1939-1943"...

The Resolution's Marines in Ae Fiord

At 3.30 a.m. on 9th May, 1940, during the operations against Narvik, when H.M.S. Resolution (Captain, now Rear-Admiral, O. Bevir) was lying off Tjelsund, the Northern Spray (Lieutenant-Commander D. J. B. Jewitt, R.N.), an anti-submarine trawler, came alongside and asked permission to discharge wounded. While on patrol she had sighted a German troop-carrying aircraft, which had been damaged by one of the Ark Royal's Skuas, making a forced landing in Ae Fiord. A party of two officers and 12 ratings from the Northern Spray and her sister ship, the Northern Gem, had set out to invesitgate in a Norwegian puffer. They had seen a party encamped on the cliffs of the fiord, closed the shore and fired on them from the sea. The Germans had returned the fire, with the result that two officers and five men from the trawlers were missing, and six wounded. Some of the missing men were believed to have been taken prisoner. The survivors had returned to the Northern Spray.

At 4 a.m. Captain Bevir called Major G. V. Walton, the Senior Royal Marine Officer, to his cabin for a conference with Lieutenant- Commander Jewitt. It was decided to land the whole of the Resolution's Royal Marine detachment, with a working party of four ratings, and two naval signalmen, to round up the German troops and to rescue the British prisoners of war.

The landing party (three officers and about 100 men, with a machinegun section, commanded by Major Walton) embarked in the Northern Spray at 7.30 a.m. They carried 24 hours' emergency rations in canvas bags, besides tea, sugar and milk in bulk. A lieutenant of the Royal Norwegian Navy, accompanied the party as interpreter.

At Ladogen, on the western entrance to Tjelsund Fiord, the party picked up the Northern Gem, and a Norwegian pilot. The German aircraft had come down on the southern side of Tepkilnisset promontory in Ae Fiord, and Major Walton decided to land on the northern side of the hill, which was about 1,000 feet high, with the object of taking the enemy in the rear.

Since it was doubtful whether the trawlers could go up the fiord, two puffers were procured, and the landing party embarked in them, towing the trawlers' four lifeboats.

The force reached the northern side of the promontory at 2.30 p.m. The water was too shallow for the puffers to go right in, so the trawlers' boats ran a shuttle service to the shore and landed the party without opposition. Major Walton then sent one platoon to advance along either bank of a stream which ran down the hill, and another to work its way along the coast to Tepkilnet village. He himself went ahead with two scouts. There was heavy snow on the ground and the rate of advance was under one mile an hour.

On the crest of the hill immediately above the village three open camps were found. The first contained British equipment, the other two German. They had evidently been abandoned in haste, for personal kit, four Tommy guns, ammunition and food were lying scattered in all directions. A British steel helmet had "S.O.S." scrawled upon it in chalk.

The marines continued their advance and swept down the steep hillside towards the aircraft. It was lying on the rocky foreshore, with one wing submerged in shallow water, the other buckled against the cliff. It was a Dornier 26, a type of civil flying-boat used by the Lufthansa in peace time on the South Atlantic service, and converted for troop-carrying. The position of the bullet holes showed that it had been shot down from above. After the guns, ammunition and documents had been taken from the aircraft, the force re-embarked in the puffers, which had rounded the promontory with the boats and were lying in the little bay below the hill.

Skirmish at Undereulet

All this time there had been no sign of the enemy, but the Norwegian officer suggested that the prisoners might have been taken to Soetran, a hamlet of half a dozen houses about six miles farther up Ae Fiord. Excorted by the Nothern Spray, the puggers accordingly proceeded to Soetran, where Lieutenant A. D. Comyn landed with his platoon and searched the village. It was empty, but showed signs of hasty evacuation. The platoon re-embarked and the force returned to the head of the fiord.

Major Walton then received information from the Resolution that the Germans were at Skjellesvik, a village lying to the south of Soetran and connected with it by a half-made road. The Norwegian lieutenant and the pilot landed to confirm the information by telephoning to Skjellesvik and the neighbouring villages, but reported that they could obtain no news of the enemy. Nevertheless, Major Walton decided to investigate. The Puffers were sent back and the force proceeded in the Northern Spray.

It was devious course by sea and it was midnight by the time they reached Skjellesvik. The inhabitants came out to meet the trawler in their boats (in those high latitudes there is no darkness at that time of year) and reported that the Germans and their prisoners were at Undereulet, a small village in a bay two miles to the northward.

There was no road between the two villages, and the bay was enclosed by steep cliffs. Rather than make a frontal landing by boat, however, Major Walton decided to send Lieutenant J. L. Carter with his platoon inland along the road to Soetran, with orders to swing to the left behind a saddleback hill and take the village in the rear. He himself made his way along the beach with the remainder of the detachment. The Northern Spray was to close the beach and give covering fire.

Some of the villager's volunteered to act as guides, but it was a hazardous and difficult march. The frontage was no more than ten yards, with sheer cliffs on the one side and deep water on the other. The marines had to advance in single file, with no room to manoeuvre, and the rocky shore made the going slow. It took over two and a half hours to cover the two miles.

As the marines approached, the Germans ran out of the house in which they were living and took up a defensive position at the base of the hill behind the village. They were driven out by the Northern Spray's 4-inch gun and the detachment's machine-guns, manned by the ratings and some of the marines under Sergeant Coulson. This undoubtedly saved Major Walton's party from attack as they were forming up. The marines then charged through the village with bayonets fixed. The Germans did not await their assault, but broke and retreated up the hill, leaving behind tommy guns, rifles, bombs and ammunition.

The marines surrounded another house, which appeared to be occupied by the enemy. The doors were locked, so they began to assault through the windows. They were about to get to work with the bayonet when they were hailed by a Cockney voice and discovered that the occupants were the prisoners from the Northern Spray, dressed in German uniforms. The wounded pilot of the aircraft was also in the house, lying on a bed. He and the rescued men were sent back to the Northern Spray, while the marines pursued the retreating Germans, supported by gunfire from the trawler.

Round-up

Since Lieutenant Carter's platoon might appear on the crest of the hill at any moment, Major Walton stopped the pursuit and ordered "Cease Fire," content to leave the enemy to his detached party.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Carter's platoon, accompanied by the Norwegian lieutenant, marching towards Soetran, had reached an empty wooden building which had been used to house the road labourers. It contained bunks, a kitchen and a telephone. It was then 3.30 a.m. - broad daylight. The platoon had been marching through heavy snow - it had covered only five miles in three hours - and Lieutenant Carter could see that without skis it would be impossible for his men to cross the deep virgin snow to the hill over which the enemy was expected. He realized that if the Germans did appear they would make for the road. Therefore, having posted sentries, he occupied the house and let his men have a meal.

An hour later the sentries reported the enemy crossing the saddleback. They were making for the house, doubtless attracted by the smoke. The marines advanced upon them through the fir trees, firing as they went. In a few minutes ten of the Germans flung down their rifles and held up their hands. Two lay wounded in the snow. The prisoners were searched, relieved of their stick grenades and pistols, and taken back to the house, the wounded being brought in on bunks from the workmen's quarters. They proved to be troops from the Jaeger Battalion and had been on their way to Narvik when the Dornier was shot down.

Lieutenant Carter took the party on to Soetran, the prisoners carrying their wounded. At 10 a.m. they reached the village, where they were picked up by a puffer and joined the remainder of the party on board the Resolution at 5 p.m., after an expedition which had lasted 34 hours. There had been no time for sleep and the marines returned tired out but elated, with the satisfaction of having accomplished their task with complete success.

As a little bit of trivia; while he was attached to the New Zealand Navy Bill was billeted out with a family in Whangerei, New Zealand.